Market Update: Caveat Emptor

Quality assurance fees don't make the grade...

Key Findings: Comparison shopping for iPhone 15 128GB refurbished across 11 UK retailers reveals systemic market dysfunction: identical “Excellent” grade labels span £99 price range (25% variance) due to non-standardised definitions. Industry grading standard exists (CTIA v5.0, July 2025) but shows low adoption in UK retail sample. Marketplace platforms (Back Market, Reboxed) add mandatory 1-1.5% checkout fees branded as “quality assurance,” extracting buyer-side margin on top of 10-15% seller commissions. Advertised prices understate actual ASPs.

It’s a bloody good job I like spreadsheets. They come in especially handy this time of year when buying a refurbished phone is on the cards to replace one of the kids’ much older refurbished phones. I usually relent when the battery percentage visibly counts down as they’re playing Clash Royale.

After a year of publicly commenting on the sector, this year’s consumer experience was especially interesting. I usually plump for n-2, and as Apple has slowly become ingrained into the family tech ecosystem, historically for access control, there’s little need for me to procrastinate over which replacement device to choose and the Google search is pretty straightforward, returning a range of tempting offers.

But that’s about as simple as it gets. From then on, out comes Excel…

Grading Standards

It’s a topic that’s been on the conference agenda for years and there’s good reason. The consumer question is usually what’s the best value within my price range? But best requires comparing like for like, which for my iPhone 15 128GB is where the spreadsheet came in.

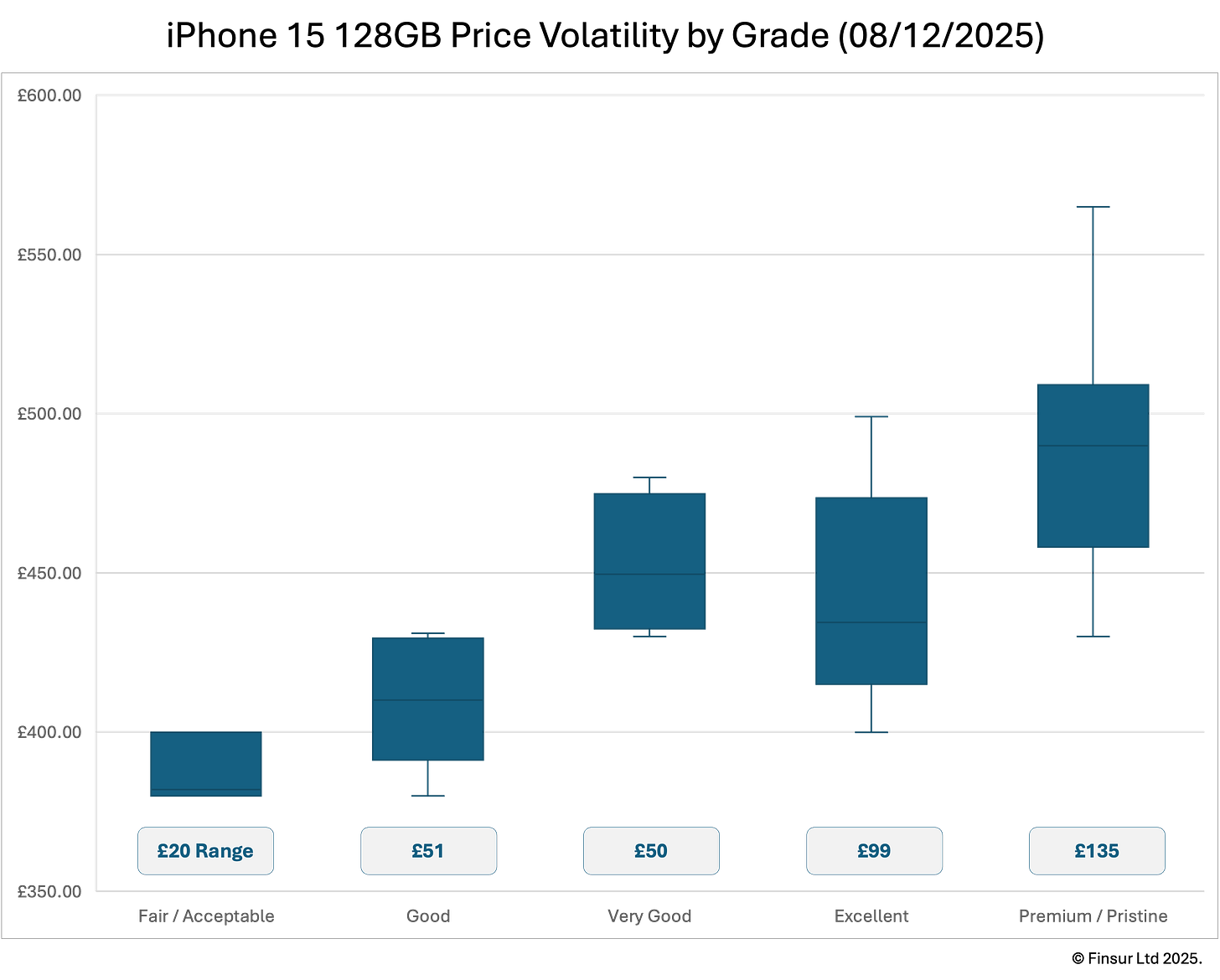

Examining the top-tier (whatever they call it) from each seller: Back Market Premium: £458; iOutlet A+: £490; MusicMagpie Pristine: £565; out-of-stock Apple Certified £509 aren’t comparable because each seller defines their top grade differently. Looking at the “Excellent” label specifically highlights the problem: Smart Cellular £399.99, Back Market £429, Currys £499. That’s a £99 spread and a 25% variance for a device in the same nominal condition. Even more striking is MusicMagpie’s ”Pristine” at £565 which exceeds Apple’s own certified refurbished device pricing by 11%. A third-party refurbisher commanding a premium over the manufacturer suggests an explanation beyond condition grading.

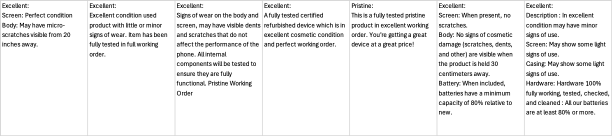

So is the £99 spread explained by market dynamics, or are these fundamentally different products wearing the same label? Examining the definitions reveals the answer. Smart Cellular’s Excellent “may have visible dents and scratches” and Back Market’s Excellent will have a “perfect screen”. They are not equivalent products and definition variability explains the wide price range. Screen standards diverge, casing standards diverge and battery specifications add a third dimension but often the clearest differentiator. The quantitative nature of battery condition (80%, 85%, 90%) is far easier to define than subjective terms like pristine or excellent.

The market exhibits complete price-grade incoherence. Devices graded ‘Very Good’ command higher median prices than those graded ‘Excellent,’ with ‘Very Good’s’ entire price range falling within Excellent’s distribution. It suggests either systematic grade inflation by lower-priced retailers or that the grade nomenclature has decoupled entirely from actual condition.

That incoherence is exactly what industry standards are attempting to address. In July this year, the CTIA released version 5 of their Wireless Device Grading Scales and Definitions standard. The document aims to provide a “common lexicon and process for grading wireless devices” including a scale for cosmetic grading and a functional testing reference. Cross-referencing the cosmetic grade with the functional test score results in a standardised classification applicable to smartphones, feature phones, tablets, wearables, and smartwatches.

As an alternative or possibly as an addition to the CTIA approach, there’s the SERI R2v3 standard which requires its own grading Q&A to help map their grades to the CTIA grades along the lines of: If a wireless device is considered a 0 (fully functional) and A (like new condition) on CTIA’s functional and cosmetic scales, then the device would be an F6 (like new) and C7 (certified pre-owned) on the REC categories. Or how about, if a device that’s a 1 and A-B (from “like new condition” to “light wear and tear” on the CTIA scales) would be F5 (refurbished) and C6 (used excellent) in the REC. Or even, a device that’s a 2 and A-D (from “like new condition” to “heavy cosmetic damage with cover lens cracks”) on the CTIA scales…you get the idea. Clearly, both approaches target B2B trading given that the consumer is a very long way from whoever engineered these grading systems.

Hidden Fees

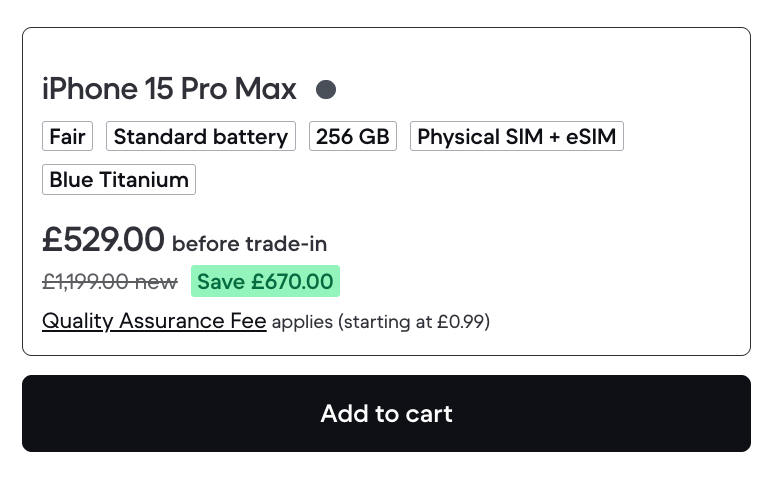

So after finding a way through the maze of definitions, a flawless condition, 90% minimum battery promise with original parts at £458.15 seemed to me, the best value at the top end of my price range that should survive a teenager’s daily Clash Royale habit. Everything else checks out and into the basket it went. But hold on, what’s this £6.49 Quality Assurance Fee? Something that warrants further scrutiny, that’s what!

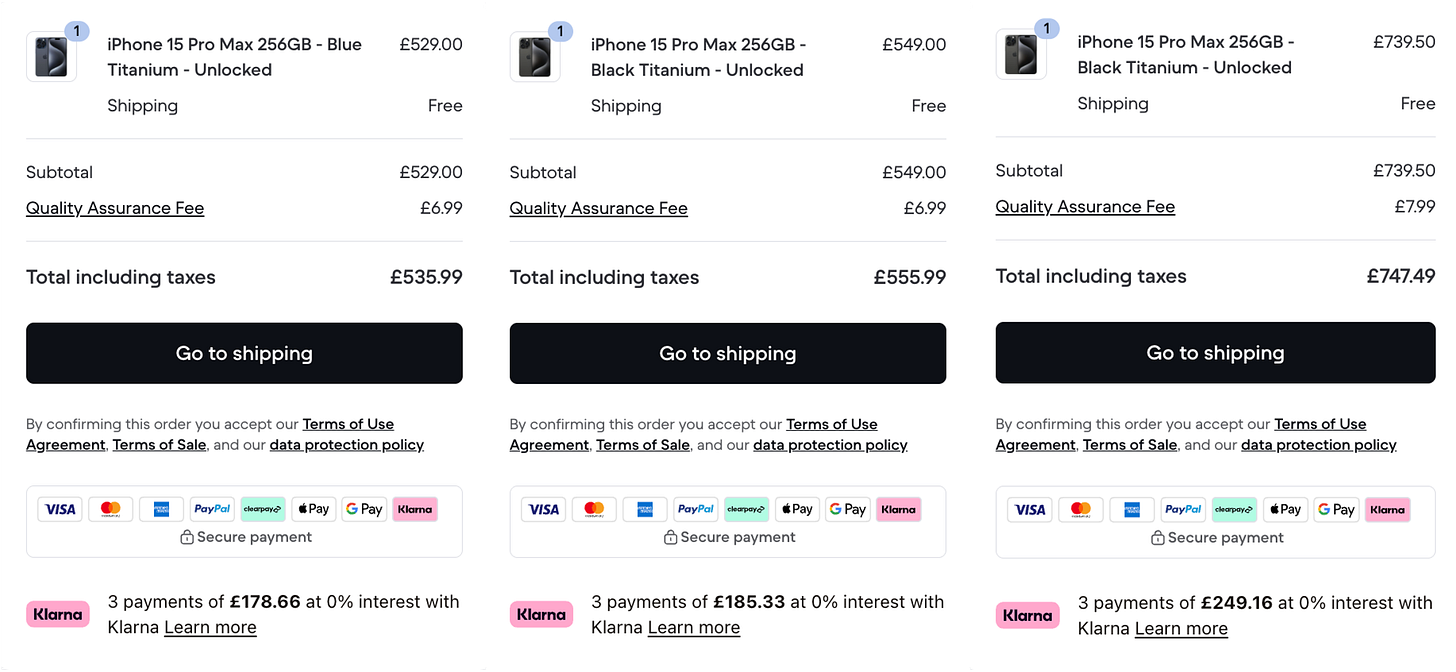

Skipping back to the product page for another look, there’s a note stating “Quality Assurance Fee applies (starting at £0.99)”. To understand the fee model I selected a different device and looked at the grade prices again:

iPhone 15 Pro Max Fair (£529): Quality Assurance Fee £6.99

iPhone 15 Pro Max Good (£549): Quality Assurance Fee £6.99

iPhone 15 Pro Max Excellent (£611): Quality Assurance Fee £7.99

iPhone 15 Pro Max Premium (£739.50): Quality Assurance Fee £7.99

So the pattern, albeit with limited testing, appears to be that the Quality Assurance Fee scales with the device value, not the service rendered:

Lower-priced devices (£458): £6.49 fee (1.42% of price)

Mid-range devices (£529-£549): £6.99 fee (1.28-1.32%)

Higher-priced devices (£739): £7.99 fee (1.08%)

Quality assurance conventionally means verifying that the product meets stated specification before shipping. This has always been a baseline expectation, not a separately chargeable service and Back Market’s fee structure suggests this is a variable commission rather than a service charge. The “Starting at £0.99” disclosure on the product page psychologically anchors consumers to the minimal fee, while the actual fee at checkout is 6-8x higher.

The headline device price appears on comparison sites, Google Shopping, casual browsing, but the consumer’s checkout price is only revealed after time and effort has been invested in the selection process. Classic. Competitive headline price, extract margin at the point of commitment. Competitors showing an all in price of £465 lose the initial comparison even though the final checkout prices are identical.

Beyond first world mild annoyance, this feels sharp for a sector already battling with trust issues1. Interest piqued, I went back through my longlist to identify other sellers doing the same thing and found only one other instance; Reboxed offering TechCheck® at £4.99 for a good grade and £5.99 for Excellent/Great grades. Same characteristics: variable pricing scaling with device value and branded as quality / inspection services. These buyer-side fees are completely separate from Back Market’s seller side commission structure, the primary engine of marketplace economics.

Business Model Economics

A marketplace exists to connect sellers and buyers and the majority of revenue will come from seller-side commissions which are usually within the 10-15% range depending on the product category. Fee granularity can go further with additional commission levels for different brands within a specific product category. There are also monthly subscription fees paid for by the seller, which feels like a far more natural location for a Quality Assurance Fee, and security deposits withheld from sellers for 13-24 months.

For a £458 iPhone 15, the economics look like this: the seller pays Back Market a monthly subscription fee of £75 and then approximately 10-15% commission (£46-£69) on the transaction. The buyer pays the £6.49 Quality Assurance Fee. Back Market’s total take on that transaction is roughly £52-75, or about 11-16% of the device price. The seller also has funds withheld as security deposit for 13-24 months to cover potential returns and warranty claims, working capital that’s tied up in Back Market’s system rather than reinvested in inventory. At scale, these mechanics matter: small percentage points multiplied across millions of transactions.

This fee structure reveals why marketplaces unbundle charges rather than showing all-in pricing. The £458 headline price drives traffic and ranks competitively in search results. The £6.49 fee extracts additional margin at checkout when the consumer has already invested time in selection. The 10-15% seller commission remains invisible to buyers. Each revenue stream is optimised independently: competitive on the comparison page, profitable at the transaction point. It’s effective platform economics, even if it complicates the consumer’s “best value” calculation. Smart, but sharp.

Summary

In the November Round Up, I referred to the CMA investigation into online selling practices related to opt-in disclosures and time-limited sales2. The Quality Assurance Fee and the TechCheck® aren’t that, but sharp practice does a sector already battling trust issues no favours and I hope they don’t proliferate.

Back Market’s CEO announced expectations of $3.5bn turnover this year, presumably GMV. The company raised $510m in Series E at a $5.7bn valuation back in 2022. Those are impressive numbers for what is, fundamentally, an aggregator: marketplaces connect buyers and sellers, no different in principle from supermarkets consolidating suppliers for consumer convenience. The difference? Supermarkets stock thousands of SKUs across dozens of categories. Back Market sells refurbished electronics. The product scope is narrow, the operational complexity lower, yet the valuation multiple assumes platform magic rather than retail fundamentals.

Perhaps fee unbundling across both sides of the transaction is how you justify those multiples. Or perhaps it signals the difficulty of making marketplace unit economics work at scale in a category with thin margins and non-standardised grading. Either way: caveat emptor, fellow shoppers - whether you’re buying a device or buying into a marketplace.

Peace,

sb.